Editor’s Note: The Baha’i community of Iran has had a long and sorrowful history of persecution, some of which has already been recounted in English language sources. To provide further scholarly access to this history, particularly episodes not already documented in English, Iran Press Watch will continue to serve as a vehicle for bringing this historical research to the attention of its readers – in addition to its role of providing news and commentary on the present-day trials and tribulations afflicting the Baha’i community of Iran. In this regard, we are pleased to publish portions of a paper by one of our editors, titled: “Abdu’l-Baha’s Proclamation on the Persecution of Baha’is in 1903”, Baha’i Studies Review, vol. 14, 2007, pp. 53-67.

Editor’s Note: The Baha’i community of Iran has had a long and sorrowful history of persecution, some of which has already been recounted in English language sources. To provide further scholarly access to this history, particularly episodes not already documented in English, Iran Press Watch will continue to serve as a vehicle for bringing this historical research to the attention of its readers – in addition to its role of providing news and commentary on the present-day trials and tribulations afflicting the Baha’i community of Iran. In this regard, we are pleased to publish portions of a paper by one of our editors, titled: “Abdu’l-Baha’s Proclamation on the Persecution of Baha’is in 1903”, Baha’i Studies Review, vol. 14, 2007, pp. 53-67.

Abstract

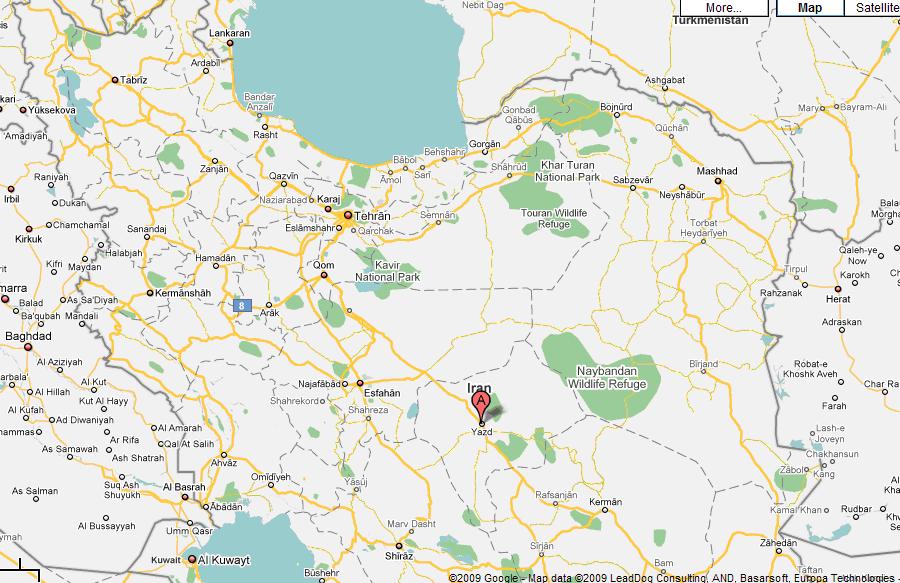

This is a provisional translation of an account by ‘Abdu’l-Baha of the persecutions of the Baha’is of Iran that erupted in 1903. There were outbursts in Rasht and Isfahan followed by a pogrom in Yazd which resulted in over 100 deaths. This account by ‘Abdu’l-Baha was originally translated and published in the United States as though the author were Haji Mirza Haydar ‘Ali Isfahani. The present retranslation is based on the original text.

Introduction

By 1903, the Baha’i community of Iran had experienced nearly a half century of relative peace. The last widespread persecution of its members had occurred in 1852-53, in the bloodbath that followed the unsuccessful attempt on Nasiru’d-Din Shah’s life by a few disgruntled Babis. During this period the community had changed its character from a militant messianic Babi community, to a peace-loving, ethically-bound, progressive-minded Baha’i community that had grown considerably in numerical strength and geographic spread. Throughout this interval though the Baha’is periodically continued to be harassed, and on occasions a few of them killed by their opponents often as excuse for political ambitions, no large scale persecution was witnessed. This changed drastically in the summer of 1903 when a pogrom was unleashed against the community, resulting in the murder of nearly two hundred defenceless Baha’is. This occurrence outraged ‘Abdu’l-Baha who wrote at length about the details and it is a rendering of this treatise that is the subject of this paper.

As the Qajar dynasty was drawing the last breath of its despotic rule, the situation for Baha’is also drastically worsened. In 1886, Mirza ‘Ali-Asghar Khan (c.1859-1907), titled the Aminu’s-Sultan, became Nasiru’d-Din Shah’s trusted prime minister and for the next 12 years (with a short break in 1897-8) ruled the central administration with tyrannical hands. During his tenure, Iran’s foreign debts grew considerably, a national revolt was raised against his disastrous tobacco concession and considerable unrest was formed against his rejection of any suggestion for social and political reform. By 1903, political opposition against the prime minister’s reactionary rule had gathered significant strength.

At first, the northern provinces, particularly the city of Rasht, rose against non-indigenous institutions such as schools. The Baha’is, as always, were used as a diversion. On 3 May 1903 a minor incident over a photograph between two Baha’i goldsmiths in Rasht, Mashhadi Taqi and Mashhadi Rida, escalated into widespread disturbance and only the prudent intervention of the governor prevented bloodshed and calmed the troubled waters.

In late May, as result of the instigation of the notorious Shaykh Muhammad Taqi, known as Aqa Najafi, over 200 Baha’is of Isfahan were forced to take refuge in the Russian Consulate while the mob pillaged their homes. Two Azali brothers were killed on trumped up charges. Through the intervention of the British and Russian Consulates, the situation subsided.

In Yazd the situation was considerably different. Aqa Najafi had written letters to all major cities encouraging them to follow his lead in harassing the Baha’is. The newly appointed prayer leader of Yazd, Sayyid Muhammad Ibrahim, arrived on 12 June and was anxious to prove his orthodoxy and to consolidate his authority. Therefore, before even arriving at the city, he circulated rumours about a general massacre of the Baha’is. The day after his arrival witnessed the first attacks against several Baha’i shopkeepers. The first murder of a Baha’i took place on 15 June when Haji Mirza Halabi-Saz was brutally killed. After that, for a week, the city was calm but soon the Baha’i-killing spread to the nearby villages and cities.[1] During the next month, wave upon wave of mob attacks left hundreds of Baha’is homeless, nearly 200 of them dead, and many more injured.

When this attempted genocide reached its peak in the midsummer of that year, ‘Abdu’l-Baha wrote a proclamatory treatise outlining events leading to this pogrom, the motives and actions of the principal persecutors, and the intense sufferings of the Baha’i community. Like all his communications on such subjects, ‘Abdu’l-Baha was full of praise for the patience, forbearance and the conduct of the Baha’is, young and old.

In retrospect, it appears that ‘Abdu’l-Baha intended this treatise to be published in the West, galvanizing the support of prominent Baha’is, Baha’i communities of the United States and Europe in general, and the public at large. Towards this end, he instructed one of his secretaries, Dr Younis Khan Afroukhtih, to translate this treatise, which presumably was done in collaboration with some of the English-speaking Baha’is visiting ‘Akka at the time. This work was further assisted by an English-speaking pilgrim of Jewish descent from Hamadan, Dr Arastoo Hakim, and was completed on 19 September 1903.

The translated treatise was then sent to the United States to be published under the title Bahai Martyrdoms in Persia in the Year 1903 AD. It was received in Chicago on 29 October 1903 and its publication took place through the work of the Baha’i Publishing Society in 1904. However, for reasons not clear to the present translator, it was published as a document prepared by Haji Mirza Haydar ‘Ali, a prominent Baha’i residing in Haifa at that time. The following notation was included:

“In compliance to the holy command of Abdul-Baha, the following account of the recent martyrdoms in Persia, up to the present time, is herein written and submitted for the perusal of the beloved of God.”

(Signed) Hadji Mirza Heider Ali.

In preparation for its publication, the Baha’i Publishing Society minimally edited the English for a smoother reading and revised a quotation from the New Testament to bring it in line with copies of the Bible available to the general public.

In the spring of 2004, the present translator coordinated a typing effort to enable the 1904 publication to be posted on the Internet for the use of researchers in Babi-Baha’i history. In April 2005, Dr Khazeh Fananapazir brought to my attention that this document was indeed a published treatise by ‘Abdu’l-Baha in Makatib ‘Abdu’l-Baha, vol. 3, pages 122-47.

This important discovery facilitated a retranslation of the treatise, which appears below. In the course of the present effort, it was further discovered that the original translation differed considerably from ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s treatise: sections were moved around, large segments from the original text were missing in the published translation, various additions were made in the translation that were not in the original text, and a number of other deficiencies were noted. Therefore, I thought it necessary to undertake a fresh translation as part of my project to collect and assemble a number of documents relating to 1903 Baha’i persecution. And while undoubtedly my translation also suffers from important shortcomings, it is more aligned with the original text and hopefully offers a basis for more befitting renderings in the future.[2]

[1] For instance, in the nearby town of Manshad, 25 Baha’is were killed most brutally over a period of ten days. See Ahang Rabbani and Naghmeh Astain, ‘The Martyrs of Manshad,’ World Order, 28/1 (Fall 1996), 21-36.

[2] In process of this retranslation, I benefited from several valuable suggestions of Dr Fananapazir and Phillip Tussing. All imperfections in this translation however, are to be ascribed to me alone.

To be continued …

Leave a Reply